The education system in Afghanistan is in a deplorable condition. The country has a 28% literacy rate which is substantially lower than its neighboring countries where the rate for Pakistan is 37% and for Iran 80%. More than three decades of war and infighting has affected Afghanistan’s infrastructure and caused higher education to suffer.

The education system in Afghanistan is in a deplorable condition. The country has a 28% literacy rate which is substantially lower than its neighboring countries where the rate for Pakistan is 37% and for Iran 80%. More than three decades of war and infighting has affected Afghanistan’s infrastructure and caused higher education to suffer.

After getting my PHD, to serve my people I will share my skills and experience with them and will fulfil it as follow: As everyone knows, Slovakia is considered one of the advanced industrial country.

Slovak people with their olden hands have found their way to great success. I want to use this scientific technical success of our friend country of Slovak republic and practice that in Afghanistan. When I get the technical and manufacture engineering knowledge and experience from Slovakia then, I will offer and present it to our own young generation to put the future of our country as advanced industrial country as Slovakia does. The research I do during my PHD period ,will try my best to gather all of them together and will change it to a research school, I will pave the ground for our talented youth to attending the school ,will practice and make my achievements feasible with my students in the area of Manufacturing Technology . The result I achieve from my research projects I will practice it in Afghanistan to develop production engineering, by doing this, so through this I can serve my people and their level of life and economy will be increased.

I. INTRODUCTION

In Afghanistan higher education is provided by public and private higher education institutions. Afghanistan currently has 19 public and more than 75 private higher education institutions. The latter were only recently established. As a result of the tremendous growth seen in private higher education institutions, the MoHE (Ministry of Higher Education) is currently pursuing a policy halting the establishment of private universities. The foremost and oldest universities, Kabul University, Kabul Medical University and Polytechnic, are all situated in the capital Kabul. The higher education curriculum is drawn up by the MoHE. The universities, both public and private, have some autonomy in contributing to the curriculum.

University and higher professional education Universities generally only offer bachelor’s and master’s degree programmes. Afghanistan has scarcely been able to develop master's programmes due to the various wars. Under the National Higher Education Strategic Plan, Afghanistan had planned to establish a range of master’s degree programmes within a few years. Master’s degree programmes are currently offered in teaching and engineering. In the past year several private universities also launched master’s degree programmes. These were primarily established in collaboration with international universities from various countries, such as Sweden, Germany, the United States of America and the United Kingdom.

II. ADMISSION TO HIGHER EDUCATION

In order to gain admission to higher education, students are required to sit a national examination after having obtained the 12 Grade Graduation Certificate. If they pass the examination, students can gain admission to a specialization within a degree programme, depending on their grades and own interests. The entrance examination is organized once each year. If students fail the examination, they are required to sit the examination a year later. The entrance examination is not an admission requirement for the private universities.

A. Bachelor

A general introduction to the programme is given in the first year. In the following years, the courses are tailored to a specific field. Only a few programmes, depending on the specialisation, incorporate work placements. In the majority of programmes, writing a thesis does not form a component of the curriculum. After obtaining a bachelor's degree, students may transfer to the master's degree programme or enter the labour market. There is no standard designation for bachelor’s diplomas. Depending on the era and regime, the term used on the document is Diploma or Certificate. In recent years the designation used is Bachelor of Arts / Science. The bachelor’s degree programmes usually have a nominal duration of 4 years, or 8 semesters.

With a nominal duration of 5 years or more the Bachelor of Engineering and the Bachelor of Veterinary Medicine are among the programmes that form an exception to the above.

The degree programme in medicine currently has a nominal duration of 7 years, including one preparatory year and a 1-year work placement at the end of the study programme. Students obtaining good konkur results do not need to pursue the preparatory year. This means that the duration of the programme will be shorter for some students. Upon completion of the programme, students are awarded the degree of Medical Doctor (MD).

B. Master

At present a limited number of master's programmes are offered in Afghanistan. Master’s programmes have a nominal duration of 2 years and are mainly offered at in some governmental Faculties and some private higher education institutions. The study programmes commenced as recently as 2013.

C. PhD

Afghanistan does not offer any PhD programmes. However, plans are currently being developed to create PhD programmes within a few years. From 2013 Afghanistan has phD programmes only in Pashto and Farsi languages.

III. REVIEW HIGH EDUCATION SYSTEM

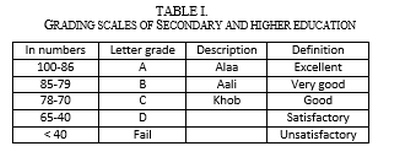

In the Afghan education system one grading scale is used for both secondary and higher education. Grades range from 0 to 100. A grade below 40 for a specific subject is deemed unsatisfactory.

Some private higher education institutions use the ECTS system. However, it is not yet recognised as the official grading system by the MoHE.

IV. QUALITY ASSURANCE AND ACCREDITATION

The MoE (Ministry of Education) and MoHE share responsibility for the entire education system, with the MoE assigned responsibility for all the education following primary education, including religious education (Madrasah) and technical and secondary vocational education up to class 14. The MoHE is responsible for higher education and drafts legislation and sets out rules for assuring the quality of both public and private universities. Due to the wars accreditation is still in the process of being developed. The MoHE recently initiated internal evaluations of the public universities. At present the MoHE has insufficient capacity available to monitor and assure the quality of the private universities. The Afghan government, however, has established clear criteria for the establishment of new private universities. The institution is required to provide a high-quality curriculum, a list of lecturers and an infrastructure. It is common knowledge that a number of private universities provide a higher standard of education than the public universities.

V. INTERNATIONAL TREATIES

Afghanistan has concluded various treaties with UNESCO in recent years. For instance, in 2013 the Ministry of Education signed a contract with UNESCO to improve primary and secondary education. The country has also concluded various treaties with multinational organisations, such as UNDP, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the European Commission to raise the standard of both secondary and higher education.

VI. HIGHER EDUCATION ENROLLMENT IN AFGHANISTAN IS ONE OF THE LOWEST IN THE WORLD

The higher education gross enrollment ratio (GER) is about 5 percent. This is one of the lowest higher education participation rates world-wide. Among countries comparable to Afghanistan, in terms of income per capita and/or their geographical locations close to Afghanistan, only three countries, Burundi, Chad and Eritrea have lower higher education enrollment rates. Countries with per capita incomes closest to Afghanistan, such as Guinea, Rwanda and Togo, have higher gross enrollment rates.

A. There are two main reasons for the low enrollment in higher education in Afghanistan

First, the 1980s and 1990s were a turbulent and violent period in the country, and education attainment levels declined. This affected all levels of education, including higher education. Second, education attainment among women is particularly low in Afghanistan. The three percent enrolled in higher education consists disproportionately of male students. Females comprised only 19% of all students enrolled in public universities and higher education institutions in 2012 [MoHE (2013)]. Low female enrollment is partly due to the smaller number of girls compared to boys in the secondary school system, which reduces the pool of women available to move on to higher education. However, it is also partly due to the lack of sufficient transport services, and sanitation and residential facilities in campuses, for young women to attend university. Also, in some cases, young women eligible to enter university may also be mothers, in which case the absence of adequate child care facilities such as crèches and nurseries are also important constraints to female enrolment.

VII. AFGHANISTAN WILL NEED TO EXPAND ENROLLMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION OVER TIME

There is strong demand for higher education from secondary school completers, and the pressure for expansion is already being felt in both public and private higher education institutions. The Government of Afghanistan (GoA) needs to develop a rational and efficient strategy for E3 increasing higher education enrollment. Expanding the enrollment of young women would be particularly important. To achieve this, Afghanistan will need to provide for facilities that female students and staff consider very important, such as adequate sanitation on-campus, secure residential facilities, and safe transportation for female students. Increasing female enrollment in universities is a top priority for the future development of higher education.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The contribution is sponsored by VEGA MŠ SR No 1/0367/15 prepared project „Research and development of a new autonomous system for checking a trajectory of a robot“ and by KEGA MŠ SR No 006STU-4/2015 prepared project „University textbook "The means of automated production" by interactive multimedia format for STU Bratislava and Kosice“.

REFERENCES

[1] P. Altbach, and J. Salmi, The Road to Academic Excellence: The Making of World – Class Research Universities. Directions in Development Series. The World Bank. Washington DC. Asia Pacific Quality Assurance Network (APQN). Retrieved on January 20, 2013, Available from http://apqn.org/

[2] Aturupane, H., R. Gunatilaka, and M. Shojo and R. Ebenezer (2013a). Socio-economic Outcomes Associated with Educational Attainment in Afghanistan 2007/08. The World Bank SASHD Working Paper (forthcoming).

[3] World Bank Gender Assessment. The World Bank, Washington DC. World Bank Education Statistics (EdStats) Database. Retrieved February, 2013.

[4] https://www.nuffic.nl/en/home/copyright.

TEXT M. E. Qazizada, Technical University in Zvolen, Faculty of Environmental and Manufacturing Technology, Department of Machinery Control and Automation Technology, Zvolen, Slovak Republic